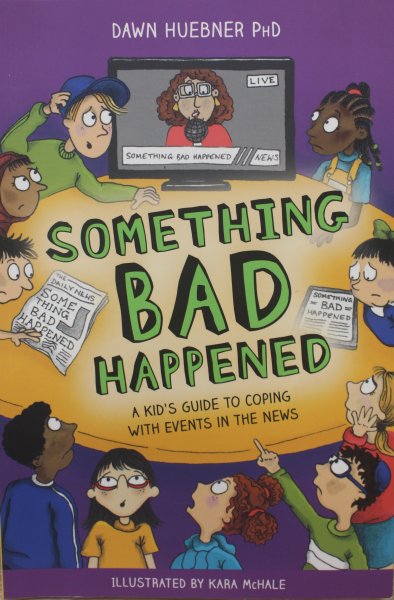

Something bad happened

Dr Dawn Huebner is a clinical psychologist specialising in the treatment of anxious children. Her latest book Something Bad Happened guides children and the adults who care about them through tough conversations about serious world events in the news. Here she tells Daniel Sinclair about the book and her motivation for writing it

Tell us a little about you and your background

Tell us a little about you and your background

I am a clinical psychologist, parent coach and author of self-help books for kids. I am also the parent of a once-seriously-anxious (now adult) son, and have at times struggled mightily myself.

What led you to become a clinical psychologist and then to specialise in the treatment of anxious children and their parents?

I always knew I wanted to work with children. When I was very young, I thought I would run an orphanage (based on the Madeline books, I think). As I got older, my interest shifted to teaching. By the time I got to college and took my first child psychology class, I knew I had found my calling. I started out as a generalist - treating anyone of any age with any set of issues - but over time, found myself most enjoying and feeling most successful with children, especially anxious children. The real turning point came when I learned about cognitive behavioural therapy in a desperate bid to help my son, who had developed a debilitating fear of splinters. CBT is the treatment of choice for anxiety, and learning it was world-changing for me (as both a parent and a professional).

My first book - What to Do When You Worry Too Much - grew out of my new understanding of how to conceptualise and treat anxiety. After publishing that book, I was inundated with referrals. Narrowing my practice while continuing to develop my expertise seemed a logical step and has worked out well.

You use the terms lower-case anxiety and upper-case Anxiety. What do you mean by those?

Lower-case anxiety is "normal". It is related to things that most people would feel anxious about – like violence, tests and performance situations, public speaking. Lower-case anxiety is transient, meaning it goes away when the stressor is gone, or it simply fades over time. It's amenable to logic, and comfort. Upper-case Anxiety can be about anything. It's sometimes an add-on to or an exacerbation of lower-case anxiety.

Here's an example: two children hear about a shooting in a far-away town. Both children feel lower-case anxious, as well they should. Shootings are scary, and it makes sense to worry whether that could happen in your town, to you or someone you love. A child who doesn't struggle with upper-case Anxiety can be comforted by caring adults. Their fears can be empathised with, and adults can reassure them about their own safety. Over time (anywhere from several hours to several weeks), their fears will fade and disappear.

But for a sub-set of children, that's not the way it goes. Lower-case anxiety turns into upper-case Anxiety. They ask for reassurance that they are safe every day. They avoid going to public places. They think about what they could use to defend themselves if a "bad guy" came in. They stop going upstairs alone, and don't want to sleep alone. I see children who refuse to go to public venues (restaurants, sports events), or who insist on sitting facing the door (so they can be the first to see the bad guy), or who do things like order drinks from glass bottles, not because they want the drink but because they want to have a weapon (the bottle) should an intruder come in. That's upper-case Anxiety.

Upper-case Anxiety sometimes attaches itself to "normal" things that it makes sense to be worried about, and sometimes is about things that in truth, hold very little actual threat - things like dogs, storms, germs, making mistakes (the list is rather endless).

Why have you written this book about dealing with things in the news now?

Something Bad Happened grew out of this recognition that there was a difference between lower-case and upper-case Anxiety, and that the way to respond to each was different.

With "normal", lower-case anxiety, comfort, reassurance, the use of logic, and distraction all make sense and are helpful. But these very responses become counter-productive when dealing with upper-case Anxiety. My prior books focus on strategies to help with upper-case Anxiety, but I hadn't written - nor have I ever seen - something to help kids with lower-case anxiety, especially about the world situation.

I want to underline that Something Bad Happened is meant to help children reacting to scary world news that has not happened to them directly. It is not a trauma book, and does not provide strategies for children who themselves are victims of violence, or homelessness, or who have had major losses. Instead, it is a book that guides children through the process of hearing about (rather than experiencing) bad news on the world stage. This is a really important distinction.

What are some of the common mistakes adults make in talking to children about the news?

The most common mistake is not talking about the news! The second most common mistake is not protecting children from hearing about the news. It may seem like these statements contradict one another, but what I mean is that we don't want children to casually hear bad news - to overhear it for example, either by hearing bits and pieces of adult conversations or to hear it on the television or radio. We want adults to make strategic decisions about which pieces of world news to share with children, and why. And then for adults to talk to children in well thought-out ways.

So, an adult might tell a child about a piece of bad news because they suspect that the child will hear about it anyway. Or they might tell about an act of violence because they need to educate their child about safety, or they want to talk about broader issues like racism. When adults do talk to children about bad news (and again, this isn't personal bad news, but instead, bad news that does not impact the child directly), they should start by finding out what the child already knows, saying something like, "Something sad happened in a church, have you heard about it?" When providing details, adults should give the basics while skipping "gory" details.

In the book I give seven pointers to caregivers when having conversations with children about the news. These are:

- Monitor your own reaction.

- Ask your children what they already know.

- Use simple terms and skip the gory details.

- Remember that even bright children are still just children.

- Maintain routines.

- Focus on the positive.

- Watch for changes.

You write about the difference between being afraid and being in danger. Can you explain what you mean by that?

There is a part of our brains tasked with keeping us safe. When that part - the amygdala - senses potential danger, it sets off an alarm. The word “potential” is important. We sometimes have "false alarms", meaning we get one of these internal danger signals - and feel afraid - when we aren't actually in danger. An example of this would be riding a roller-coaster. The amygdala registers the height and speed and mechanics of the ride and sets off a danger alarm, when really these rides are quite safe. The same thing happens when we see a scary movie or read a scary book - we feel afraid (the amygdala pulls the alarm) - but we aren't actually in danger.

Often we can make quick assessments about actual risk, and then we act accordingly. For example, if you are walking down the street and you hear a loud bang, you might initially think, "Gunshot!" but then you realise an old car just went by, and the sound isn't continuing, and no one around you is panicking, and you realise, "Oh, the car backfired" and you are no longer afraid. But this system of having a danger alarm go off in our heads and making the assessment of actual risk can go awry, which is the distinction between lower-case and upper-case Anxiety. In upper-case Anxiety, people stop assessing actual danger, or they do so incorrectly.

So, how do we deal with these false alarms?

Once a danger alarm is triggered in the brain, the thinking parts of the brain (temporarily) shut down. We need to calm ourselves to re-access logical thinking. Breathing and mindfulness techniques are a great way to do this, to calm a triggered brain. They are most helpful when learned in advance, and practiced, and then coached by a supportive adult.

It is tempting to quiet the false alarm by accommodating it ("Oh, you're afraid of bees? Then we won't go to that park with the flowers because there might be bees there.") but this is a mistake. Accommodation quiets fear in the moment but cements it in place in the long run.

In addition to breathing and mindfulness activities, empathy helps to quiet a brain that's been triggered. So, having a supportive adult say something like, "That was scary." or "Your brain told you our house could burn down, too. No wonder you felt so frightened." Empathy helps to re-integrate the brain, getting children back to more logical thinking so they can better hear and take in the comfort, logic, or support adults are offering.

The final chapter in the book is about how doing something positive can help how we feel. Can you give an example of how that works practically?

This is based on something young climate activist Greta Thunberg says, that there is a connection between hope and action, so that when we are feeling despair (about the world situation, for example), rather than reaching for hope, we should reach for action, because action - positive action - leads to hope. I want children to understand this, so I've included something about it in my book.

Doing something positive always helps. It shifts the focus away from the helplessness we feel about a scary thing we've heard about and towards the good thing we are going. It makes us part of a community of helpers, working on the side of love and inclusion and safety for all. Positive actions can be small - being kind to someone who is different from you, showing up for a protest, gathering toys to donate to less fortunate kids - but even small actions make a difference, both in adding to the collective good and in improving mood and outlook. So, the message is not "take hope", the message is "do something positive", in part because it will help you feel better/more hopeful. This is true for adults as well as kids.

What advice would you give to foster carers when it comes to talking about bad events in the news?

It's important for foster carers to recognise that the children in their care have been traumatised, and that trauma can be re-triggered. So, feeling sad or scared about something that happened to someone else is likely to remind children in foster care of their own sadness and fear, related to their own situation. Children in foster care often feel powerless; they are moved, and things happen to them, without their input or consent. Helplessness and fear go hand-in-hand. The more powerless we feel, the more afraid we feel (and often angry, too). Talking to foster children about news on the world stage is still important to do. I hope that books like mine will teach children a set of coping skills they can use to deal with the fear, sadness, and confusion they might feel when hearing bad news, and can pave the way for sensitive, feelings-based discussions.

Something Bad Happended is available from online booksellers for about £10.